The first woman to found a bank and grant Black Americans access to credit.

By

Lani Allen

It was 1904 in Richmond, Virginia, when Maggie Lena Walker led her community in a city-wide boycott of segregated street cars. “Our self respect demands that we walk,” she declared. Her refusal to accept the segregationist laws of the Jim Crow south foreshadowed what many recognize as the official start of the Civil Rights Movement fifty years later: Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat. Though far-less recognized, Walker’s show of strength and leadership demonstrated that the movement had begun long before then, and with Walker at its helm.

The daughter of a former slave, Walker was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1864, just one year after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Dedicated to the empowerment of a community just beginning to experience freedom, yet continuously burdened by oppressive Jim Crow laws, she became the first Black woman (and woman, period) to found and run a bank. She was also the first to give her community access to credit, just one of many trailblazing triumphs she would make in her lifetime.

When Walker was growing up, most women of color still worked in roles of servitude. “I was not born with a silver spoon in my mouth, but with a laundry basket basically on my head,” she described. As a girl, she and her mother would wash the clothing of wealthy white people for a living.

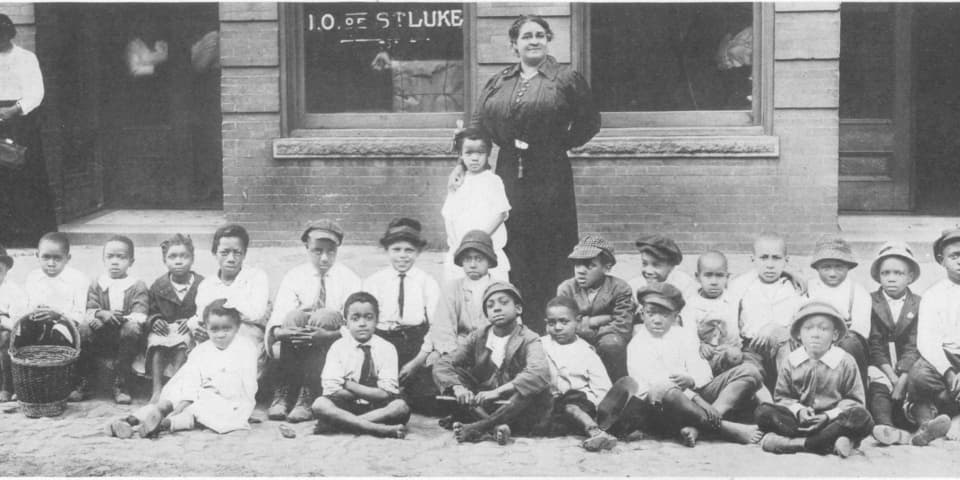

Despite this, Walker graduated high school and went on to become a teacher for three years. At the same time, she followed in her mother’s footsteps as an active participant of the Independent Order of St. Luke (IOSL), a fraternal burial society that administered to the sick and aged, promoted humanitarian causes, and encouraged individual self-help and integrity. Walker lived these principles, and her dedication to the IOSL eventually earned her the highest position of Grand Secretary in 1899. By then, however, the organization was on the verge of bankruptcy.

Nothing stopped her. In an attempt to bolster the organization, she quickly acted on a vision to create businesses that hired and served members of the Black community, encouraging her community to put their money where people valued them, towards people who shared their struggle. Under her leadership, the IOSL opened a department store, created a newspaper, and - most importantly - founded The St. Luke Penny Savings Bank (St. Luke Bank).

“Let us put our moneys together and have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars,” she advocated. For the first time, local Black-owned businesses were given what they needed to grow and thrive.

In her tenure as Grand Secretary, Walker would grow the IOSL to over 100,000 members across 24 states.

At the turn of the century, Black Americans were completely excluded from the financial system. Married white women could not even have their own bank accounts until the 70s. The new President of her institution, Walker recognized that the majority of banks measured risk through the lens of race and gender, excluding the large population of people who not only wished to take out loans, but were also quite able to pay them back.

So she devised an alternative measure of risk: work ethic and moral character. The St. Luke Bank tapped into local community networks to evaluate applicants’ credit-worthiness based on these new criteria. By listening to her community, she also discovered that there was high demand for smaller loans. In offering loans as little as $5, the St. Luke Bank was able to reach much farther into the Black community - and help more people.

By 1920, the St. Luke Bank’s assets rose to $530,000, what would be $7 million today.

While the bank sought to empower all of her community, the Department Store was where Walker enacted her vision to empower financial independence for Black women, whom she felt had been dealt the “short end of the stick” in the “race of life, in the struggle for bread, meat and clothing…” Located on Richmond’s main shopping avenue, the store employed only Black women, and featured only Black mannequins in the windows inviting shoppers to come in and purchase their Sunday Best.

Meanwhile, her newspaper, The St. Luke Herald, gave her community a voice to speak out against crimes and injustices harming Black Americans, including lynchings that were happening regularly and at record-numbers: “The persecution of our people must be told. Somebody must… cry aloud,” she implored.

Walker’s trailblazing accomplishments shone through as undeniable markers of her legacy. Perhaps clouded by the passage of time, however, were the constant battles she fought against white opposition to keep her businesses alive.

For one, the state banking commissioner, an avid proponent of shutting down Black banks, forced Walker to cease lending to both the newspaper and her department store. In 1905, when she moved the St. Luke Bank into the department store, white merchants threatened to boycott vendors who supplied the store. The landlord who owned the building next door also threatened to open a saloon in order to attract unsavory clientele, thus making the department store an unattractive place to shop. Tragically, their efforts were successful, and ultimately drove the store out of business.

The bank, however, survived. In fact, it thrived. After merging with two other Richmond-based banks, Walker proceeded to serve as chairman of the board of the new Consolidated Bank and Trust Company (CBTC), and successfully steered the organization through the Great Depression.

Throughout her life, Walker’s accomplishments tangibly improved the lives of tens of thousands of Black Americans in Richmond and beyond. Her work demonstrated that granting fair access to financial tools and resources was critical to empowering financial freedom and independence.

Walker also taught us an important lesson on the power of data science in granting access to the financial system to those who were previously excluded from it. Met with a population barely one generation freed from slavery, she knew their financial history - or lack thereof - did not accurately reflect their credit-worthiness. By identifying new measures of risk and using the resources she had on hand to evaluate said risk, Walker was actually practicing an early form of data science. Her innovative approach also enabled her to better understand the needs and demands of her community, allowing her audience to influence the size and types of loans she offered.

Her strategies worked. The CBTC would go on to prosper as the oldest continuously Black-operated bank in the United States until 2009, when it was acquired by the Premier Financial Bancorp., Inc.

As Mission Lane strives to increase access to credit among the fifty percent of Americans who are still underserved by the financial industry, we have a lot to learn from Maggie Lena Walker. Many families still suffer the effects of generations of discrimination that have not only left them with a general distrust of the financial system, but also with far fewer resources to draw on when faced with financial strife.Today’s heavy reliance on credit scores to determine someone’s credit-worthiness allows this exclusion to persist.

At Mission Lane, we know that scores alone fail to capture someone’s intent, commitment, and ability to pay off loans. That’s why we have invested in technology that goes beyond the score to capture our applicants’ fuller financial pictures. We also recognize the value of harnessing data to generate insights into credit-worthiness, and are committed to investing in opportunities where data can inform more inclusive product development.

A pioneer in banking and data science, Walker blazed the trail for us to follow. It is now up to us to learn from our past and think critically about the future as we aim to increase fair access to financial health.